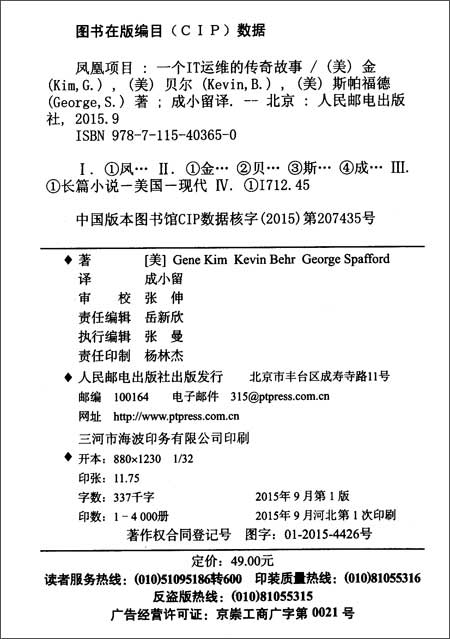

On the Sense of Humor

Lin Yutang

[Lead-in]

This selection is from Lin Yutang’s The Importance of Living, which is regarded as one of his most famous books and a grand synthesis of his philosophy. “It became the best-selling book in America in 1938, was translated into a dozen languages, and secured for him the position of a leading interpreter of China to the West.”(Lin Taiyi). Humorously but logically, Lin expresses the Chinese way of life as well as the oriental sentiment of romance in his book, which can be clearly seen in the following selection.

[1] I doubt whether the importance of humor has been fully appreciated, or the possibility of its use in changing the quality and character of our entire cultural life—the place of humor in politics, humor in scholarship, and humor in life. Because its function is chemical, rather than physical, it alters the basic texture of our thought and experience. Its importance in national life we can take for granted. The inability to laugh cost the former Kaiser Wilhelm an empire, or as an American might say, cost the German people billions of dollars. Wilhelm Hohenzollern probably could laugh in his private life, but he always looked so terribly impressive with his upturned mustache in public, as if he was always angry with somebody. And then the quality of his laughter and the things he laughed at—laughter at victory, at success, at getting on top of others—were just as important factors in determining his life fortune. Germany lost the war because Wilhelm Hohenzollern did not know when to laugh, or what to laugh at. His dreams were not restrained by laughter.

[2] It seems to me the worst comment on dictatorships is that presidents of democracies can laugh, while dictators always look so serious—with a protruding jaw, a determined chin, and a pouched lower lip, as if they were doing something terribly important and the world could not be saved, except by them. Franklin D. Roosevelt often smiles in public—good for him, and good for the American people who like to see their president smile. But where are the smiles of the European dictators? Or don’t their people want to see them smile? Or must they indeed look either frightened, or dignified, or angry, or in any case look frightfully serious in order to keep themselves in the saddle? ...

[3] We are not indulging in idle fooling now, discussing the smiles of dictators; it is terribly serious when our rulers do not smile, because they have got all the guns. On the other hand, the tremendous importance of humor in politics can be realized only when we picture for ourselves a world of joking rulers. Send, for instance, five or six of the world’s best humorists to an international conference, and give them the plenipotentiary powers of autocrats, and the world will be saved. As humor necessarily goes with good sense and the reasonable spirit, plus some exceptionally subtle powers of the mind in detecting inconsistencies and follies and bad logic, and as this is the highest form of human intelligence, we may be sure that each nation will thus be represented at the conference by its sanest and soundest mind. Let Shaw represent Ireland, Stephen Leacock represent Canada; G. K. Chesterton is dead, but P. G. Wodehouse or Aldous Huxley may represent England. Will Rogers is dead, otherwise he would make a fine diplomat representing the US; we can have in his stead Robert Benchley or Heywood Broun. There will be others from Italy and France and Germany and Russia. Send these people to a conference on the eve of a great war, and see if they can start a European war, no matter how hard they try. Can you imagine this *bunch [= group] of international diplomats starting a war or even plotting for one? The sense of humor forbids it. All people are too serious and half-insane when they declare a war against another people. They are so sure that they are right and that God is on their side. The humorists, gifted with better horse-sense, don’t think so. You will find George Bernard Shaw shouting that Ireland is wrong, and a Berlin cartoonist protesting that the mistake is all theirs, and Heywood Broun claiming the largest share of *bungling [ßbungle:vi.办糟,搞砸] for America, while Stephen Leacock in the chair makes a general apology for mankind, gently reminding us that in the matter of stupidity and sheer foolishness no nation can claim itself to be the superior of others. How in the name of humor are we going to start a war under these conditions?

[4] For who have started wars for us? The ambitious, the able, the clever, the *scheming [adj.诡计多端的], the cautious, the *sagacious [adj.有洞察力的, 有远见的, 精明的, 敏锐的], the *haughty [adj.傲慢的], the over-patriotic, the people *inspired [受神灵启示的] with the desire to serve mankind, people who have a “career” to carve and an “impression” to make on the world, who expect and hope to look down the ages from the eyes of a bronze figure sitting on a bronze horse in some square. Curiously, the able, the clever, and the ambitious and haughty are at the same time the most cowardly and muddleheaded, lacking in the courage and depth and subtlety of the humorists. They are forever dealing with trivialities, while the humorists with their greater sweep of mind can *envisage [正视, 面对] larger things. As it is, a diplomat who does not whisper in a low voice and look properly scared and *intimidated [胆怯的] and correct and cautious is no diplomat at all... But we don’t even have to have a conference of international humorists to save the world. There is a sufficient stock of this desirable commodity called a sense of humor in all of us. When Europe seems to be on the *brink [边缘] of a catastrophic war, we may still send to the conferences our worst diplomats, the most “experienced” and self-assured, the most ambitious, the most whispering, most intimidated and correct and properly scared, even the most anxious to “serve” mankind. If it be required that, at the opening of every morning and afternoon session, ten minutes be devoted to the showing of a Mickey Mouse picture, at which all the diplomats are compelled to be present, any war can still be *averted [转移].

[5] This I *conceive [认为] to be the chemical function of humor: to change the character of our thought. I rather think that it goes to the very root of culture, and opens a way to the coming of the Reasonable Age in the future human world. For humanity I can visualize no greater ideal than that of the Reasonable Age. For that after all is the only important thing, the arrival of a race of men *imbued [v.浸透] with a greater reasonable spirit, with greater *prevalence [流行] of good sense, simple thinking, a peaceable temper and a *cultured [有教养的] outlook. The ideal world for mankind will not be a rational world, nor a perfect world in any sense, but a world in which imperfections are readily perceived and quarrels reasonably settled. For mankind, that is frankly the best we can hope for and the noblest dream that we can reasonably expect to come true. This seems to imply several things: a simplicity of thinking, a *gaiety [n.欢乐的气氛] in philosophy and a subtle common sense, which will make this reasonable culture possible. Now it happens that subtle common sense, gaiety of philosophy and simplicity of thinking are characteristic of humor and must arise from it.

[6] It is difficult to imagine this kind of a new world because our present world is so different. On the whole, our life is too complex, our scholarship too serious, our philosophy too *somber [adj.阴森的,忧郁的], and our thoughts too involved. This seriousness and this involved complexity of our thought and scholarship make the present world such an unhappy one today.

[7] Now it must be taken for granted that simplicity of life and thought is the highest and *sanest [最健全的] ideal for civilization and culture, that when a civilization loses simplicity and the sophisticated do not return to unsophistication, civilization becomes increasingly full of troubles and degenerates. Man then becomes the slave of the ideas, thoughts, ambitions and social systems that are his own product. Mankind, overburdened with this load of ideas and ambitions and social systems, seems unable to rise above them. Luckily, however, there is a power of the human mind which can transcend all these ideas, thoughts and ambitions and treat them with a smile, and this power is the subtlety of the humorist. Humorists handle thoughts and ideas as golf or *billiard [台球] champions handle their balls, or as cow boy champions handle their *lariats [套马索]. There is an ease, a sureness, a lightness of touch, that comes from mastery. After all, only he who handles his ideas lightly is master of his ideas, and only he who is master of his ideas is not enslaved by them. Seriousness, after all, is only a sign of effort, and effort is a sign of imperfect mastery. A serious writer is awkward and ill at ease in the realm of ideas as a *nouveau riche [爆发户] is awkward, ill at ease and self-conscious in society. He is serious because he has not come to feel at home with his ideas.

[8] Simplicity, then, paradoxically is the outward sign and symbol of depth of thought. It seems to me simplicity is about the most difficult thing to achieve in scholarship and writing. How difficult is clarity of thought, and yet it is only as thought becomes clear that simplicity is possible. When we see a writer *belaboring [belabor vt.<古> 就...作过分的冗长的讨论或分析等] an idea we may be sure that the idea is *belaboring [belabor vt.<古>痛打, 不断辱骂和嘲弄] him. This is proved by the general fact that the lectures of a young college assistant instructor, freshly graduated with high honors, are generally *abstruse [adj.深奥的] and involved, and true simplicity of thought and ease of expression are to be found only in the words of the older professors. When a young professor does not talk in *pedantic [adj.书生气的] language, he is then positively *brilliant [adj.有才气的], and much may be expected of him. What is involved in the progress from *technicality [n.专门性, 学术性] to simplicity, from the specialist to the thinker, is essentially a process of digestion of knowledge, a process that I compare strictly to *metabolism [新陈代谢]. No learned scholar can present to us his specialized knowledge in simple human terms until he has digested that knowledge himself and brought it into relation with his observations of life. Between the hours of his *arduous [adj.费劲的, 辛勤的] pursuit of knowledge (let us say the psychological knowledge of William James), I feel there is many a “pause that refreshes,” like a cool drink after a long fatiguing journey. In that pause many a truly human specialist will ask himself the all important question, “What on earth am I talking about?” Simplicity presupposes digestion and also maturity: as we grow older, our thoughts become clearer, insignificant and perhaps false aspects of a question are *lopped [lop vt.修剪, 砍伐]off and cease to disturb us, ideas take on more definite shapes and long trains of thought gradually shape themselves into a convenient formula which suggests itself to us one fine morning, and we arrive at that true luminosity of knowledge which is called wisdom. There is no longer a sense of effort, and truth becomes simple to understand because it becomes clear, and the reader gets that supreme pleasure of feeling that truth itself is simple and its formulation natural. This naturalness of thought and style, which is so much admired by Chinese poets and critics, is often spoken of as a process of gradually maturing development. As we speak of the growing maturity of Su Tungpo’s prose, we say that he has “gradually approached naturalness”-a style that has *shed [摆脱] off its youthful love of *pomposity [华丽], *pedantry [n.炫学, 卖弄学问], *virtuosity [精湛技巧] and literary *showmanship [n.演出的技巧].

[王小波,李银河,王道乾[情人],毕淑敏,余华,都梁]

[9] Now it is natural that the sense of humor nourishes this simplicity of thinking. Generally, a humorist keeps closer touch with facts, while a theorist dwells more on ideas, and it is only when one is dealing with ideas in themselves that his thoughts get incredibly complex. The humorist, on the other hand, indulges in flashes of common sense or wit, which show up the contradictions of our ideas with reality with lightning speed, thus greatly simplifying matters. Constant contact with reality gives the humorist a bounce, and also a lightness and subtlety. All forms of pose, sham, learned nonsense, academic stupidity and social humbug are politely but effectively shown the door. Man becomes wise because man becomes subtle and witty. All is simple. All is clear. It is for this reason that I believe a sane and reasonable spirit, characterized by simplicity of living and thinking, can be achieved only when there is a very much greater prevalence of humorous thinking.

----- Excerpted from The Importance of Living

论幽默感

林语堂

[1] 我很怀疑世人是否会体验过幽默的重要性,或幽默对于改变我们整体文化生活的可能性——幽默在政治上,在学术上,在生活上的地位。它的机能与其说是物质上的,还不如说是化学上的。它改变了我们的思想和经验的根本组织。我们须默认它在民族生活上的重要。德皇威廉因为缺乏笑的能力而丧失了一个帝国,或者如一个美国人所说,使德国人民损失了几十万万元。威廉二世在私生活中也许会笑,可是在公共场所中,他的胡须总是高翘着,给人以可怕的印象,好像他永远在跟谁生气似的。并且他那笑的性质和他所笑的东西——因胜利而笑,因成功而笑,高居人上而笑,——也是决定他一生命运的重要因素。德国战败是因为威廉二世不知道什么时候应该笑,或对什么东西应该笑,他的梦想是脱离笑的管束的。

[2] 据我看来最深刻的批评就是:民主国的总统会笑,而独裁者总是那么严肃——牙床凸出,下唇鼓起,下唇缩进,像煞是在做一些非可等闲的事情,好像没有他们,世界便不成为世界。——罗斯福常常在公共场所中微笑,这对于他是好的,对于喜欢看他们总统微笑的美国人也是好的,可是欧洲独裁者们的微笑在哪里?他们的人民不喜欢看他们的微笑吗?他们一定要装着吃惊、庄严、愤怒或非常严肃的样子,才能保持他们的政权吗?

[2] 现在我们讨论独裁者的微笑,并不是无聊的寻开心:当我们的统治者没有笑容时.这是非常严重的事,他们有的是枪炮啊。在另一方面只有当我们冥想这个世界,由一个嬉笑的统治者去管理时,我们才能够体味出政治上的重要性。比如说,派遣五六个世界上最优秀的幽默家,去参加一个国际会议,给予他们全权代表的权力,那么世界便有救了。因为幽默一定和明达及合理的精神联系在一起,再加上心智的上的一些会辨别矛盾、愚笨和坏逻辑的微妙力量,使之成为人类智能的最高形式,我们可以肯定,必须这样才能使每一个国家都有思想最健全的人物去做代表。让萧伯纳代表爱尔兰,史梯芬·李可克(Stephen Leacock)代表加拿大;却斯透顿(G. K. Chesterton)已经死了,可是伍德好司(P. G. Wodehouse)或爱多斯·赫胥黎(A1dous Huxley)可以代表英格兰。威尔·罗杰(Will Rogers)可惜已经死了,不然也倒可以做一个美国代表;现在我们可以请劳勃·本区雷(Robert Benchlhey)或海·胡德·勃朗(Hey Wood Broun)去代替他。意大利法国德国俄国也有她们的幽默代表,如果派遣这些人物在大战的前夕去参加一个国际会议,我想无论他们怎样拼命地努力,也不能掀起一次欧洲的大战来。你会不会想象到这一批国际外交家会掀起一次战争,或甚至计谋一次战争。幽默感会禁止他们这样作法。当一个民族向另一民族宣战时,他们是太严肃了,他们是半疯狂的。他们深信自己是对的,上帝是站在他们这一边的。具有健全常识的幽默家是不会这么想。你可以听见萧伯纳在大喊爱尔兰的错误的,一位柏林的讽刺画家说一切错误都是我们的,勃郎宣称大半的蠢事应由美国负责,可以看见李可克坐在椅子上向人类道歉,温和地提醒我们说.在愚蠢和愚憨这一点上,没有一个民族可以自誉强过其他民族。在这种情形之下,大战又何至于能引起呢?

[3] 那么是谁在掀起战争呢?是那些有野心的人、有能力的人、聪明的人、有计划的人、谨慎的人、有才智的人、傲慢的人、太爱国的人,那些有“服务”人类欲望的人,那些想创造一些事业给世人一个“印象”的人,那些希望在什么场地里造一个骑马的铜像,来睥睨古今的人。很奇怪地,那些有能力的人、聪明的人、有野心的人、傲慢的人,同时,也就是最懦弱而糊涂的人,缺乏幽默家的勇气、深刻和机巧。他们永远在处理琐碎的事情。他们并不知那些心思较旷达的幽默家更能应付伟大的事情。如果一个外交家不低声下气地讲话,装得战战兢兢、胆怯、拘束、谨慎的样子,便不成其为外交家。——事实上,我们并不一定需要一个国际幽默家的会议来拯救这世界。我们大家都充分地潜藏着这所谓幽默感的东西。当欧洲大战的爆发,真在一发千钧的当儿,那些最劣等的外交家,那些最“有经验”和自信的,那些最有野心的,那些最善于低声下气讲话的,那些最会装得战战兢兢、拘束、谨慎的模样的,甚至那些最切望于“服务人类”的外交家,在他们被派遣到会议席上去时,只稍在每次上午及下午的开会议程中,拔出十分钟的辰光来放映米老鼠影片,令全体外交家必须参加,那么任何战争依旧是可以避免的。

[4] 我以为这就是幽默的化学作用:改变我们思想的特质。这作用直透到文化的根底,并且替未来的人类,对于合理时代的来临,开辟了一条道路。在人道方面我觉得没有再比合理时代更合崇高的理想。因为一个新人种的兴起,一个浸染着丰富的合理精神,丰富的健全常识,简朴的思想,宽和的性情,及有教养眼光的人种的兴起,终究是唯一的重要事情。人类的理想世界不会是一个合理的世界,在任何意义上说来,也不是一个十全十美的世界,而是一个缺陷会随时被看出,纷争也会合理地被解决的世界。对于人类,这是我们所希冀的最好东西,也是我们能够合理地冀望它实现的最崇高的梦想。这似乎是包含着几样东西:思想的简朴性,哲学的轻逸性,和微妙的常识,才能使这种合理的文化创造成功。而微妙的常识,哲学的轻逸性,和思想的简朴性,恰巧也正是幽默的特性,而且非由幽默不能产生。

[5] 这样的一个新世界是很难想象的,因为它跟我们的现在的世界是那么不同。一般地讲起来,我们的生活是过于复杂了,我们的学问是太严肃了,我们的哲学是太消沉了,我们的思想是大纷乱了。这种严肃和纷乱的复杂性,使现在的世界成为这么一个凄惨的世界。

[6] 我们现在必须承认:生活及思想的简朴性是文明与文化的最崇高最健全的理想,同时也必须承认当一种文明失掉了它的简朴性,而浸染习俗,熟悉世故的人们不再回到天真纯朴的境地时,文明就会到处充满困扰,日益退化下去。于是人类变成在他自己所产生的观念、思想、志向和社会制度之下,当着奴隶,担荷这个思想、志向,和社会制度的重担,而似乎无法摆脱它。幸而人类的心智尚有一种力量,能够超脱这一切观念、思想、志向而付之一笑,这种力量就是幽默家的微妙处。幽默家运用思想和观念,就像高尔夫球或弹子戏的冠军运用他们的球,或牧童冠军运用他们的缰绳一样。他们的手法,有一种因熟练而产生的从容,有着把握和轻快的技巧。总之,只有那个能轻快地运用他的观念的人,才是他的观念主宰,只有那个能做他的观念主宰的人,才不被观念所奴役。严肃终究不过是努力的标记,而努力又只是不熟练的标志。一个严肃的作者在观念的领域里是呆笨局促的,正如一个暴发户在社交场中那样呆笨而不自然一样。他很严肃,因为他和他的观念相处还不曾达于自然。

[7] 说起来有点矛盾,简朴也就是思想深刻的标志和象征。在我看来,在研究学问和写作上,简朴是最难实现的东西。欲求思想明澈已经是一桩困难的事情,然而简朴更须从明澈中产生出来。当一个作家在促使一个观念时,我们也可说那观念在促使他。这里有一桩普通的事实可以证明:一个刚从大学里以优异的成绩毕业出来的大学助教,他的讲辞总是深奥繁杂,极其难于理解,只有资格较老的教授们才能把他的思想单纯地用着简明易解的字句表达出来。如果一个年轻的助教不用他自矜博学多才的语句来讲解时,他确有出类拔萃而远大的前途,由技术到简朴,由专家到思想家.其间的过程,根本是一种知识的消化过程,我认为是和新陈代谢的作用完全一样的。一个博学的学者,须把那专门的知识消化了,并且和他的人生观察联系起来,才能够用平易简明的语句把这专门知识贡献出来。在他刻苦追求知识的时间中(我们就假定说是詹姆斯William James的心理学知识吧),我觉得一定有许多次“心神清爽的休息”,好像一个人在疲乏的长途旅行中停下来喝一杯清凉的饮料一样。在那休息的时间中,那些真正的人类专家,会把自己反省一下,“我们到底在做什么?”简朴必须先消化和成熟,当我们渐渐长大成人的时候,思想会变得更明澈,无关紧要的一点或虚假的一面,将尽被剔去,不再骚扰我们。等到观念有了较明确的形态后,一大串的思想便渐渐变成一个简括的公式,突然地有一天在一个明朗的清晨跑进了我们的脑子,于是我们的知识便达到了真正光辉的境界。嗣后便再不用努力了,真理已变成简单易解,读者也将觉得真理本身是简易的,公式的形成是自然的,因此获得很大的快乐。这种思想上和风格上的自然性,——中国的诗人和批评家那么羡慕着——常常被视为一种逐渐成熟的发展过程。当我们讲到苏东坡的散文逐渐成熟时,我们便说他“渐近自然”——这种风格已经把青年人的爱好华丽、夸炫、审美技艺和文艺夸张等心理一概消除。

[8] 幽默感滋养着这种思维的简朴性,这是很自然的事。一般的说,幽默家比较接近事实,而理论家则比较注重观念,当一个人跟观念本身发生关系时,他的思想会变得非常复杂。在另一方面,幽默家浸沉于突然触发的常识或智机,它们以闪电般的速度显示我们的观念与现实的矛盾。这样使许多问题变得简单。不断的和现实相接触,给了幽默家不少的活力、轻快和机巧。一切装腔作势、虚伪、学识上的胡诌、学术上的愚蠢和社交上的欺诈,将完全扫除净尽。因为人类变得有机巧有机智了,所以也显得更有智慧。一切都是简单清楚。所以我相信只有当幽默的思维方式普遍盛行时,那种以生活和思维的简朴为特性的健全而合理的精神才会实现。

----------

[原著]林语堂

[翻译]越裔汉

----- 选自:林语堂《生活的艺术》,陕西师范大学出版社,2006年2月第1版

![[Sumerian] 00](https://cdnss.haodaima.top/uploadfile/2024/0328/fd8212c65689d57dae4f7ca9e62b6db6.png)